Where we are living and teaching English to children is in a part of Costa Rica not too terribly far from the Nicaraguan border—three hours, in fact, by a bumpy ride over roads both paved and unpaved.

With our program break coming up, I looked into ways to get to the historical city of Granada. It boiled down to two options: (a) get a ride somehow, by unpredictable public bus or by expensive taxi/shuttle, to the city of Liberia in Guanacaste province, then take a bus such as Tica Bus all the way up to Granada; or (b) pay one hell of a lot more money for a private van to pick us up at our door, take the three of us across the labyrinthine CR/Nica border and drop us at our Granada hotel—and do the exact reverse in a week’s time.

I opted for (b), mostly because I was warned that in this off season, with recent landslide-related highway closures outside of Costa Rica’s capital, San Jose, the long-distance bus services might be even more unpredictable than they normally are. And I was also warned about abundant pickpocketing and theft on those buses; people who put their stuff in the overhead racks run a big risk of losing their valuables as well as not-so-very-valuables.

So we’re spending a lot of money to head up to a historical city, one which itself is not the safest. Nicaragua today is the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Haiti ranks first). What’s more, around 46% of Nicaraguans are surviving on less than $1.15 a day.

It raises the question: Why? Why go there and take this risk? Why not just stay here, enjoy the beach, and relax in our relatively safe little town? Why not take all that transportation money we’ll be using, and donate it to a Nicaraguan relief agency?

A deserving Nicaraguan kid with no ability to pay for five years of high school can be sponsored very easily—-our round-trip Granada transport costs alone could send her/him to high school for two years. Businesses in Granada know this, too, and even some of the local hotels and language schools promote the charitable educational sponsorship of local kids.

I don’t think I can very easily explain this math to my sons. What we will spend there on a week’s vacation could in fact send a bright, impoverished Nicaraguan child to high school for five years—uniforms, shoes, and all.

Granada is, from what everyone says, a gorgeous, historical city with lots of opportunities to appreciate archaeology, geology, plant and animal biology, culture, and architecture, among other things. It’s Nicaragua’s number one tourist destination.

But Nicaragua is hurting. Here where we teach in Costa Rica, Nicaraguan kids sit alongside the local village kids. There is prejudice: Nicaraguans are mistrusted and looked down upon by some. Many Nicaraguans here, whether legal or illegal residents, are willing to do work for much lower pay than the Costa Ricans will accept. I walk past some of the Nicaraguan immigrant families’ places and see that they live in abject poverty, in tin shacks with few amenities. The local public school denies some of the children access to a classroom education, maintaining that it is already overcrowded. Yet what I am told here is that this place, for these Nicaraguan kids and their families, is the lap of luxury.

The game plan in Granada is this: Bring toys, educational materials, and clothing to orphanages in the area. There are orphanages in town, and a couple on nearby Ometepe Island in Lake Nicaragua. We will make an orphanage visit in Granada and will treat a group of orphaned girls to a pizza party—the nun running the place does not know this yet, of course, but since getting food is an issue for her organization, we don’t anticipate any objections from her.

And we will take a carriage ride through town and around part of the lake. It is the low season right now, and by patronizing local businesses and services, we will be helping them and their families.

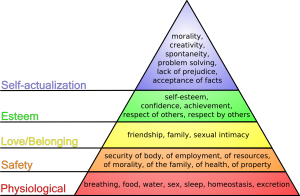

All the while, I will be discussing the economy with the kids, and helping them to understand the value of what we are seeing in Nicaragua. The essential questions will be: What do people need? What do people want? What motivates people in their existence?

I’ll call this our Maslow’s unit.

11. October 2010 at 1:10 pm

What an awesome opportunity for your children! I wish I could do the same. Then again, maybe I could! Stay safe!